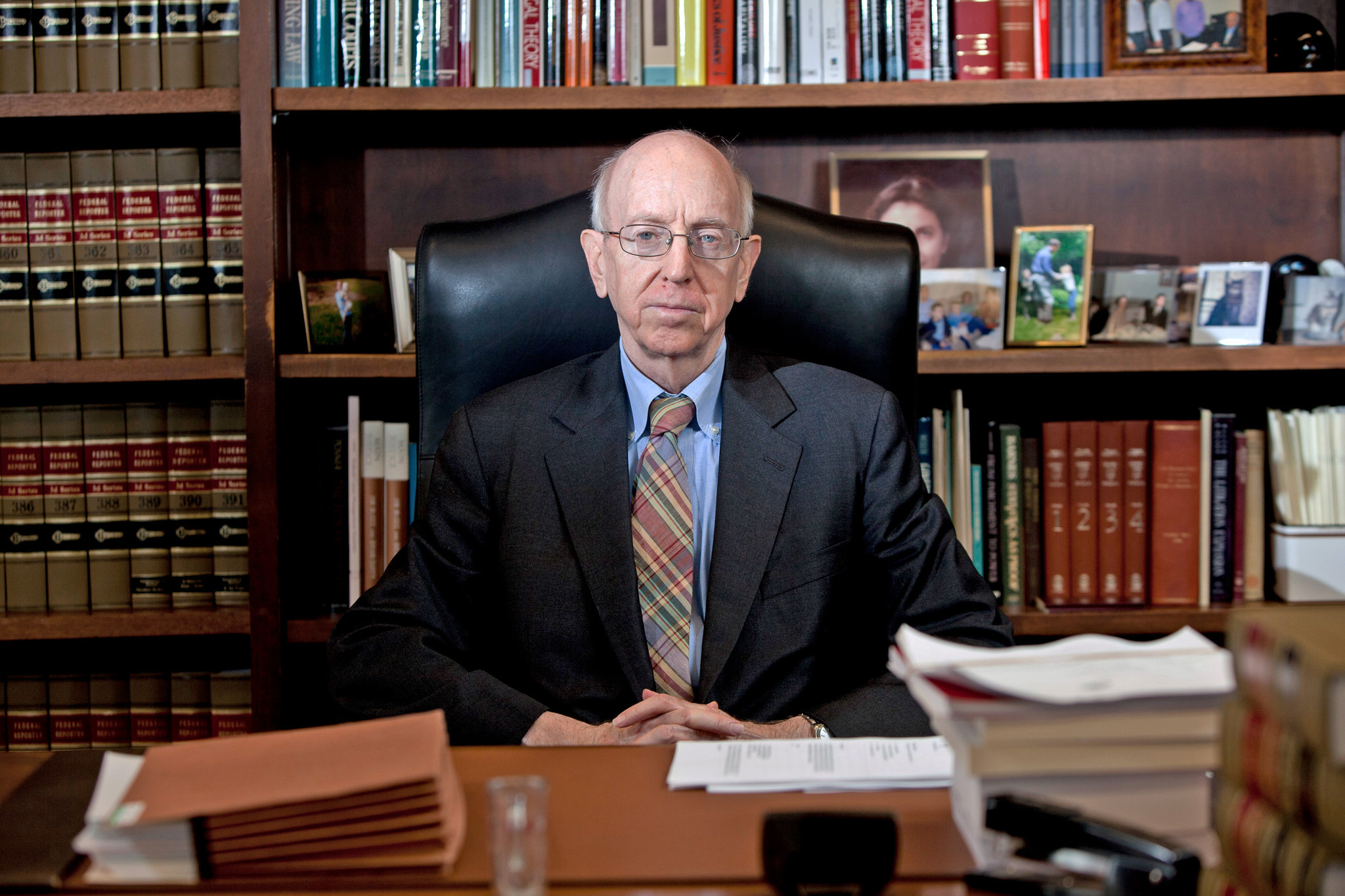

Posner's Pragmatic Adjudication

Comparison between pragmatic adjudication and judicial positivism with Judge Richard Posner at the spotlight, along with some commentaries of my own. Submitted for PHIL 2103 on May 3, 2021.

Jurisprudence, being a major pillar of American democracy and an indispensable channel for the people to redress their grievances, impacts our lives in ways well beyond the courthouse. The method of its exercise, therefore, is a matter deserving of careful examination. One of such methods which has gained increasing traction, proposed by the legal scholar Richard Posner, is pragmatic adjudication. In this paper, I will first compare and contrast the legal theory of pragmatic adjudication against that of judicial positivism. Then, I will detail what Posner means when he argues that maintaining consistency with past decisions and authorities should only be part of the equation when the pragmatic judge deems it beneficial to the present and future outcomes. Finally, I will explain Posner’s argument for the inevitability of pragmatic adjudication in our legal system by examining a case he discusses and provide my assessment of this argument.

Rejecting Ronald Dworkin’s belief that legal pragmatism is a free pass to disrespect and tramp on past precedents in the name of future welfare, Posner makes clear that pragmatic adjudication is, in fact, a theory of law that strives to achieve the best results for both the present and the future. Posner defines a judicial pragmatist, in opposition to a judicial positivist who accepts it, as one who rejects the idea that it is their duty as a judge to abide by past legal decisions and statutory authorities (7). Rather than utilizing argument from analogy and analysis of precedent based on certain presupposed universal facts of law, a judicial pragmatist gives more emphasis on the facts—that is, its particular context—when reviewing a case and then renders a decision that he or she deems conducive to the best consequences. In short, while both the pragmatist and the positivist look to the legal and statutory authorities as well as the facts of the case, the former focuses more on the facts, whereas the latter focuses more on the authorities.

Accordingly, a pragmatic judge is not, as Dworkin has hypothesized, altogether indifferent to historical and statutory authorities when making a legal decision. Recognizing there is often a trade-off between administering substantive justice in the current case and upholding law’s consistency and predictability, a pragmatic judge consults precedents and statutes as “repositories of knowledge,” but not as primary, deciding factors for their judgment. They may be willing to defer to authorities at the expense of substantive justice when such a deference is aptly justified (5). In contrast to how a judicial positivist views the case law, statute, and constitutional provision as ends in themselves, a judicial pragmatist views them as sources of information whose merits must not be “obliterated or obscured gratuitously” in determining how to bring about the best results in the current case, though this consideration ought not extent to essentially disregarding the facts of the case under review (5).

Given how pragmatic adjudication is not tethered to the application of rules, a common misconception that a pragmatic judge will always prioritize their gut reaction, or intuition, over legal materials. This is far from the case. Indeed, when a pragmatic judge has no confidence in their own and everyone else’s discretion in a certain case, they are ready to affirm past decisions, because the risk of a “merely conjectural gain” from an overrule which they have no confidence will ever occur is greater than the proven benefits of certainty and stability (8). In such circumstances, the best outcomes for the future and now are accomplished through following the established authorities.

Multiple objections to pragmatic adjudication are foreseeable. One of them is that such a discretionary justice is sure to create an abundance of uncertainty, hence thwarting predictability in law and, by extension, people’s trust in the legal system. Is law really law, as the dissenters may query, if its products are not in accordance with a set of rules? Certainly, if its results are not predictable, then the incentive to follow the law seems much less attractive. To raise this objection is to misconstrue the judicial pragmatist as a rigid follower of standards, as opposed to the judicial positivist as a rigid follower of rules, when the pragmatist is not rigid at all. Indeed, should they find a “pragmatic argument in favor of rules’’ appealing, such as that standards-based judgments create too much uncertainty as to prohibit any flexibility, the pragmatic judge is quite open to accepting it (16). Another worthy objection is that judicial pragmatists must be prone to letting their passions overtake their reason. It should be noted that judges generally possess above average experience, intelligence, and gravitas. They are not internet trolls who spout nonsense for the fun of it. The fact that judges cannot hide behind a bogus username and are expected to publicly release their judgments, especially in novel cases, enhances accountability in addition to promoting “effectiveness and self-discipline” (11).

Despite having addressed various criticisms against pragmatic adjudication and presented it as a charming candidate for a descriptive legal theory, Posner does not assert that this theory of law should be the preferred approach for courts in all nations. Just like philosophical pragmatism, judicial pragmatism may not “travel well” to countries other than the United States, especially to one with parliamentary systems that are fundamentally unicameral (18). In a parliamentary country where the legislative branch is comparatively more centralized, judges have a reasonable expectation that a lapse in the current law and the injustice borne by the citizens are only temporary and will be promptly fixed. Therefore, these judges can afford to be judicial positivists.

On the other hand, Posner believes that an American judge, at least an appellate judge, within the system of checks-and-balances does not have the luxury to choose between being a pragmatist or a positivist (18). His justification for this conclusion is multi-faceted: the tricameral nature of America as a federalist democracy, the fact that our nation’s judicial branch was initially much neglected and had to force the other two branches to treat it as equals through Madison v. Marbury (1803), the fact that judges are not selected according to a set criteria has and will continue to result in greater diversity of sitting judges in terms of “moral, intellectual, and political” inclinations, and the American spirit of individualism and anti-authoritarianism. These are substantial hindrances to judges who simply wish to apply check the boxes by referencing a rulebook—be it the Constitution, state or federal statutes, or past precedents—because the rulebook may well be outdated, conflicting, or simply absurd.

In the 1965 Supreme Court case of Griswold v. Connecticut, a case which even a dissenting Justice calls “uncommonly silly,” the issue was whether the state of Connecticut’s passing of a law that criminalizes the use of contraceptives for married couples is constitutional. Seven out of nine Justices took the pragmatic approach and inferred that the protection of privacy is intended in the Bill of Rights; hence, the Connecticut law is unconstitutional. But if the Justices were all judicial positivists, then they would reject Griswold’s argument that the state is intruding upon her privacy, because nowhere in the Constitution is the phrase “protection of privacy,” or even just the word “privacy,” ever written. Even if the Justices feel that this law is ludicrous, under judicial positivism, they would have no choice but to find it constitutional nonetheless. They could only hope that by the time the legislative branch has gotten around to repeal the law or amend the Constitution to explicitly include the protection of privacy, the substantive injustice that transpired in the meantime has not outdone their duty to uphold justice, in which case the job of a Justice would appear an entirely contradictory affair.

I agree with Posner’s argument that if judges want “the best results,” they will inevitably adopt pragmatic adjudication and look beyond the cases, regulations, and other “orthodox legal materials” (8, 19). Passing a bill in Congress is already a hard enough process, not to mention this long struggle is not guaranteed to succeed in patching the legal gaps. After the bill is referred to a committee and then a subcommittee, after thorough research and hearings are conducted, after the bill survives the filibuster and potentially damaging compromises are reached, after the bill is passed along to the president, after the president signs the bill—which may or may not happen—in cases where immediate remedies are necessary, it is quite likely that the substantive injustice done has become far beyond repair. By the time constitutional amendments have undergone their arduous legislative process, there very well could have hundreds of thousands of black children denied equal education, of innocent men and women imprisoned because they cannot afford a lawyer, or of women at the brink of mental and physical collapse because they are denied control of their own body. The law is not created in a vacuum, nor are the people it is supposed to watch over living in a vacuum. A judge need not be duty-bound to rules in order to appear exonerated of judicial impropriety, for rules are made by people, and people are imperfect creatures.

Reference Notes

(7) refers to page 7 of Richard Posner’s Pragmatic Adjudication, Cardozo Law Review (1996).