Peirce and the Method of Science

Difference between doubt and belief and how they relate to the scientific method, in the context of Peirce’s four methods of inquiry. Submitted for PHIL 2103 on March 17, 2021.

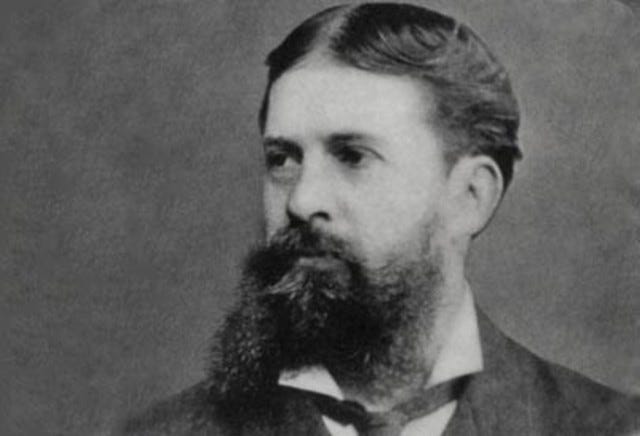

Our beliefs are the glasses we wear to make the world more comprehensible—with them on our noses we feel confident in our interpretation, without them we see the world as an impressionist painting whose form is fathomable but whose nature is blurred, and in this state we are in doubt. And when the prescription is no longer suitable, we change the glasses, and once again we see. American philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce, in our analogy, is an ophthalmologist who wishes to find a method that determines the best prescription. In this essay, I will first explicate the differences between doubt and belief that are essential to Peirce’s conclusion in his essay The Fixation of Belief that the scientific method is the method of inquiry. Then, I will interpret Peirce’s four methods of inquiry in detail. Lastly, I will put forth some of my concerns regarding Peirce’s argument and how the scientific method may address what seems unreachable by science.

Peirce outlines three main points that separate our conception of doubt and our conception of belief. The first distinction involves our intuitive inclination to “ask a question” when in doubt and to “pronounce a judgment” when in belief (1). Here we first capture a glimpse of Peirce’s conviction that these two sensations are indicative of our practical actions. Indeed, the next point of distinction Peirce enunciates is the practical difference that the beliefs we have come to embrace “guide our desires and shape our actions,” which is manifestly an indicator of some habit that leads to certain actions, whereas doubt does not serves as a predictor of our habits, nor of our actions (1). The last point of difference is that of the state each sensation puts us in. While belief escorts us to a state of tranquility and satisfaction that we wish to indulge in, doubt pins us in a state of discomfort and dissatisfaction that we cannot help but struggle to break free from in order to reach the pleasant state of belief, such is the “irritation of doubt” (1). And this irritation is the “only immediate motive” for that struggle (1). Combining all three points of distinction together, Peirce paints a pragmatic framework in which belief has an “active effect” that directs us to perform certain actions in response to some certain prompt and doubt has a reflexive effect which continues to irritate us until doubt itself is decimated.

Peirce uses the term “inquiry” to describe such a struggle to arrive at the state of belief from the state of doubt by removing that very doubt (1). Whenever we replace a belief with doubt we reject a belief simply on the grounds that the action it leads does not satisfy our desire, Peirce notes, we introduce a new irritation of doubt and, along with it, a new struggle. Therefore, Peirce concludes that the sole object of inquiry is to settle, or fixate, our opinions. That is, the process of the fixation of belief starts with a belief, then morphs into a doubt, which drives us to inquiry, and arrive at a fixed opinion through the correct method. This proposition, Peirce contends, undermines some “vague and erroneous” forms of inquiry, including Cartesian skepticism, the presumption of a priori truths, and futile arguments on established topics (2).

So here arises the need to determine the prime method of inquiry that does not lead to any further doubt. In this essay, Peirce scrutinizes four particular methods. The first is the “method of tenacity” (3). Under this method, one holds on to their existing belief as true belief out of sheer stubbornness. They consciously and deliberately avoid that which threatens their beliefs, lest it lead them astray from their established opinions. So long as this self-deception does not beget some inconveniences greater than its benefits, they reckon, this method of tenacity can provide them with satisfaction and a piece of mind. But this ostrich of a person which buries its head in the sand in exchange for the bliss of ignorance is sure to find its method feeble in practice, for they will find others’ opinions which are contrary to their own just as sound as their own, and this engenders doubt. And, Peirce emphasizes, this recognition of another’s opinion being possibly comparable to one’s own is not something we can actively suppress. Thus, the method of tenacity is not the method Peirce is after.

Peirce then moves on to discuss the method of authority under the rule of an institution, which Peirce declares to be superior to the method of tenacity in its mentality and morality. Additionally, Peirce remarks that the method of authority has been proven to be proportionally more successful than the method of tenacity throughout history—some visible proofs being the stone structures in Siam, Egypt and Europe commissioned under organized faiths whose “sublimity hardly more than rivaled by the greatest works of Nature” (4). Yet, also recorded in history is this method’s inevitable realization of “a most ruthless power,” for this is an effort of organized banishment of outsiders and the faithless, and for the method of authority to be effective, the cruelty of its punishment must be viscerally felt (4). Even so, Peirce argues, no institution can regulate with absolute certainty the opinions of its every single subject. Due to the fact that opinions shape one another in our inherently social society, even in the most “priest-ridden states,” some individuals are bound to be the black sheep among other lambs (4). Unlike the intellectually enslaved mass governed under the method of authority, these individuals observe the ways of other countries and other eras, and they come to recognize the doctrines they hold as mere accidents of the circumstances they happen to find themselves in—not of absolute truth. Hence, the method of authority, which fails to reign in these black sheeps, like the method of tenacity, also leaves room for doubt.

The a priori method, which Peirce turns to next, seems more plausible than the previous two methods due to its appeal to reason. Having shed the pride of stubborn adherence and the shackles of forced beliefs, those engaging in the a priori method rests their belief upon “fundamental propositions” that seem “agreeable to reason” (5). Peirce highlights that the major drawback of this method is precisely its reliance on these fundamental propositions, because such propositions are not derived from experience, but from our mental inclinations. As such, the a priori method considers inquiry as the “development of taste,” which is “always more or less a matter of fashion” (5). That is, the contemporary view substantially shapes how we evaluate what is of great “taste” and what is not. Therefore, even though we think we are exercising intellectual freedom using the a priori method, we are in fact a product of our taste in a given time and culture, and that introduces “accidental and capricious” elements which can lead to real doubt (5). Consequently, the a priori method is also insufficient as the method of inquiry.

All three precedingly discussed methods have contingency upon some human caprice, and all have been eliminated by Peirce as his choice of the method of inquiry. He thereby deduces that the method we need is one without human influence, one that is unaffected by our doing and thinking but holds universal truth—the method of science (6). This method’s hypothesis is that there are Real, law-abiding things independent of us interacting with each other “out there.” We come to the one and only True conclusion about how things really are—the true nature of objects—by utilizing “the law of perception,” “sufficient experience,” and enough reasoning (6). Beliefs fixated by the method of science contain in them “external permanency” universal to all and unchanged by temporal or cultural differences. They can thus fixate not only our individual beliefs, but the beliefs of the community at large, which Peirce asserts is the utmost problem in the fixation of belief due to the necessarily connected nature of our society (3). In other words, the method of science can take us from a state of doubt to a collective, common state of belief without any further doubt due to its permanency that is independent of human contribution. This is the only method among the four that accurately informs us of right and wrong.

In my view, Peirce’s methodology and structure in this essay are generally quite compelling, though I do have a few concerns. First, in his discussion of the method of tenacity, Peirce avows one’s recognition of other’s opinions as possibly equivalent to theirs an inevitable, uncontrollable impulse. I find myself searching for reasons why this impulse is indeed insuperable. Empirically speaking, it is the case that most people abide by this impulse, but it is not categorically inconceivable to think of someone so arrogant or ignorant or simply constituted such that they do not comprehend others’ opinions as belonging to the level of theirs. A crude example may be a sociopath, a mentally-ill patient, or just a madcap. My second concern is in his certainty in our ability to know the absolute reality of things as they truly are, which is a key concept that the method of science relies upon. Like Copernicus and Kant, I am of the view that the observer necessarily filters the understanding of the observed object due to their location or constitution. In our interaction with reality, it seems to me that our pure intuitions of space and time renders our understanding of objects out there merely as appearances, not as they truly are. These are, of course, a priori concepts, but Peirce does not, at least in this essay, indicate how these pure intuitions are contingent upon the era and environment I happen to find myself in.

This essay does not explicitly discuss Peirce’s view on how the method of science may handle questions seeming beyond science, like matters of religion, but it can be inferred that Peirce’s method of science will do so by assuming a one and only true conclusion to each of such questions. While the conclusions may appear unreachable by science, they are reachable by the method of science. That is, just like how we approach a regular question with the method of science, we also approach these even more abstract concepts through the method of science by the law of perception, experience, and enough reasoning. The rest, according to Peirce, will fall into place eventually, for there is but one true conclusion which is the fixation of our collective belief.

Reference Notes

(1) refers to page 1 of Charles S. Peirce’s The Fixation of Belief, retrieved from http://oregonstate.edu/instruct/phl201/modules/peirce/peirce_print.pdf