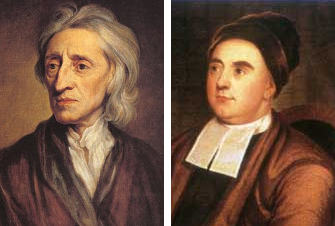

Locke and Berkeley on Existence of Substance

Kant argues in the Transcendental Dialectic that the knowledge of the self as a substance as put forth by rationalists is in fact unreachable knowledge beyond human constitution. Submitted for PHIL 2103 on November 11, 2020.

In the philosophical field of empiricism, realists and idealists dispute over the absolute existence of material substance. John Locke, an empirical realist, maintains a realist view that there is material substance existing independently outside of our mind and perception. Material substance, or matter, has in them three kinds of qualities. Conversely, the empirical idealist Bishop George Berkeley holds that material substance does not exist independently and absolutely. In what follows, I will explicate each philosopher’s position in regards to material substance through their account of primary, secondary, and tertiary qualities. First, I will interpret how Locke believes that primary qualities are mind-independent and create ideas in our mind resembling those qualities, whereas secondary and tertiary qualities do not. Then, I will outline how Berkeley rejects Locke’s position by positing that all qualities are mind-dependent.

According to Locke, ideas are “sensations or perceptions” in our mind and qualities are “the power to produce any idea in our mind” (8). In other words, an object’s qualities have the ability to cause sensations to exist in our mind, but the qualities themselves are not sensations. In his Essay, Locke categorizes qualities of objects into primary, secondary, and tertiary qualities. Primary—also known as “real, original,” or “insensible”—qualities produce simple ideas in us which resemble the objects themselves (9, 23, 24). They are constant, inseparable qualities existing in an object itself regardless of whether “we take notice or not” and irrespective of the state the object is in or the alterations it may undergo (9, 18, 22). That is, primary qualities are mind-independent and always present in the object. To hone in on this definition of primary qualities, Locke proposes that no matter how hard or frequent one mills and pestles a grain of wheat, it still maintains that no form of division can take away the grain of wheat’s primary qualities—namely, its “solidity, extension, figure, or mobility” (9). What division does is simply making “two or more distinct separate masses of the [same] matter,” but that does not separate the primary qualities from the object (9).

On the other hand, secondary qualities are the powers of the primary qualities to “produce various sensations in us … as colours, sounds, tastes, etc.” and are thus explainable and depend on primary qualities (10, 15). However, the ideas produced by secondary qualities do not resemble, nor do they exist in, the object itself (13, 15). One ought to note that Locke does not state that secondary qualities exist only in the mind and never in the objects themselves. Rather, what Locke argues is that ideas or sensations produced by the secondary qualities do not resemble their secondary qualities. For instance, our idea or sensation of “whiteness” of the snow does not resemble the quality of “white” in the snow (16). Whereas in the case of a triangle, for example, my idea of “triangularity” does in fact resemble its quality of being a triangle, which is the primary quality of figure. Further, if we take away our senses, secondary qualities inevitably “vanish and cease” and are “reduced to their causes,” which are primary qualities (17). Because secondary qualities are “nowhere when we feel them not,” that they only exist so long as we sense them, it cannot be the case that they constantly exist in the object independently of our perception faculties (17, 18). Thus, secondary qualities are also denoted “sensible qualities” (23).

Locke’s last sort of qualities are tertiary qualities, which are “barely powers” in an object that make such a change in another object’s “bulk, figure, texture, and motion” such that they produce in us different sensations from before (10, 23). An example of a tertiary quality is the sun’s ability to melt or blanch wax: we clearly recognize that the effects, which is the “whiteness and softness produced in the wax” are distinct from the object causing them, which is the sun (24). Hence, we cannot state that the idea of “meltedness” that was produced by the sun’s tertiary quality resembles the sun’s actual quality, for the sun is not melted in the sense that the wax is melted. It follows, then, that tertiary qualities do not produce in us ideas or sensations that resemble those qualities (24). The difference between secondary and tertiary qualities is that we can clearly see that the effects in the latter qualities are isolated from the object causing them, but it is harder to see this distinction in secondary qualities (24).

Berkeley offers an idealist view in contrast with Locke’s realism in his Three Dialogues through Philonous’ rejection of Hylas’ account of materialism, which Berkeley defines as a belief in the existence of material substance independent of the mind (I:1). That is, sensible things, or material substances or objects, have “a real absolute existence—distinct from, and having no relation to, their being perceived” (I:4). Instead, Berkeley argues that “sensible things can’t exist except in a mind or spirit” (I:29). That is, minds of spirits, through perception, are what create sensible things. However, this is not to say that Berkeley thinks that sensible things, or material substances, have “no real existence” (II:29). Rather, Berkeley proposes that because they “have an existence distinct from being perceived by me,” sensible things must have been perceived by another spirit (II:29). And judging from the “variety, order, and manner of these impressions,” the spirit that is perceiving sensible things must be “wise, powerful, and good” and beyond one’s comprehension (II:31). In other words, the sensible things which we perceive do not exist independently of the mind; they are created by the mind, or will, of “an infinite Spirit” which we denominate God (II:32).

To arrive at this conclusion, Berkeley intends to render all qualities, including primary qualities that Locke believes exist in the objects themselves independent of the mind, mind-dependent. Specifically, if he can prove that primary qualities, which have absolute existence and are fundamental to material substances, exist only in the mind, Berkeley will have proved that material substances do not exist independently and absolutely. First, Berkeley illustrates that secondary and tertiary qualities are non-distinguishable with the pain and pleasure argument. According to Hylas, who represents materialists, all degrees of heat, a secondary quality, have “real existence;” and real existence is possible only if a material substance’s existence does not depend on some mind’s perception of it (I:4). Hylas then agrees that pain, a tertiary quality, cannot occur in an “unperceiving thing” (I:4). That is, tertiary qualities are mind-dependent. Then, because fire creates in us “one simple idea [that] is both … intense heat and pain,” making intense heat identical to pain, which is mind-dependent, it follows that intense heat, a secondary quality, is also mind-dependent (I:5). And as all degrees of heat have in them the same “real existence,” it follows that all degrees of heat are mind-dependent (I:6). The same fate follows for other secondary qualities that are chained to the mind-dependent quality of pleasure (I:5).

However, Hylas is not so convinced of the case where “a lesser degree” of secondary qualities exist outside the mind (I:6). Berkeley counters this proposition by the relativity argument: if one puts their left which is cold and their right which is hot simultaneously into lukewarm water, it would seem to the left hand that the water is hot and to the right, cold (I:6). But to say that the lukewarm water is both cold and hot at the same time is “an absurdity” by the law of contradiction (I:6, 11). Thus, secondary qualities also exist only in our minds.

Using this conclusion as a springboard, Berkeley contends that primary qualities, like secondary qualities, also have no real existence apart from the mind’s perception (I:17). Take the example of the primary quality of extension. If we look at an “insect’s foot” as a human, we will perceive the foot’s size as much smaller than if we were to look at it from the insect’s own perspective (I:13). And as we move towards or away from an object, its size, which is part of its extension, changes (I:13). By the law of contradiction, an object cannot have a size that is both large and small. Hence, “there is no size or shape in an object” (I:14). And because “motion, solidity, and gravity” all clearly “suppose extendedness,” they too must not exist in material substances without some mind’s perception (I:15). Additionally, Berkeley highlights that primary qualities like extension and motion cannot be separated from secondary qualities (I:16). For instance, although one can easily form the word “motion” by itself, they cannot form or grasp such an abstract idea “without any particular size or shape or other sensible [secondary] quality” (I:16). Consequently, similar to the case of secondary qualities, the relativity argument can “count just as strong against the primary qualities also” (I:17). That is, primary qualities, like secondary qualities, like tertiary qualities, are mind-dependent and cannot exist if no mind is perceiving them.

In short, pursuant to Locke’s account, material substance produces ideas and sensations in us, and material substance exists whether or not a spirit perceives that substance. To Berkeley, instead of material substance, God produces those sensations, and material substance exists only in our minds or God’s mind. Berkeley’s concern with Locke’s realism is that it leads to skepticism and possibly atheism. While both philosophers agree that we are only directly aware of ideas, Locke’s inference that material objects are the causes of such ideas may warrant doubt (7). Namely, concluding that something we do not directly know actually exists appears erroneous. And because we do not immediately perceive material objects, concluding that material objects exist as the causes of our sensations seems, if nothing else, at least haste. Additionally, it seems implausible that matter can impact the mind, i.e. create sensations in them, when the two are distinct and independent from one another like Locke puts forth. Moreover, granting that material substance exists independently of some mind’s perception is to grant that its existence “doesn’t involve being perceived by God,” which invites atheism (III, 45).

At the same time, an obvious rebuttal to Berkeley’s idealism is that if there is no material substance, one may not distinguish reality from imagination. Though Berkeley responds by pointing out that ideas that are “real” are “vivid and clear” and are involuntary, because they are “imprinted on our mind” by a spirit other than us, whereas ideas formed by illusions are “dim, irregular, and confused” (III, 45). However, some imaginations and illusions are also voluntary, so judging whether it was formed voluntarily may not be the most vigorous criterion in judging an idea’s realness. Lastly, it appears that Berkeley’s implies that all causal relations are products of minds or spirits. If so, if one commits a repugnant act, it seems convenient for them to say that God, not themself, is morally responsible. Berkeley says that “sin or wickedness does not consist in the outward physical action or movement, but in the internal,” or the “laws of reason and religion,” though this argument may not occur convincing to those who do not believe in the laws of religion (III:46). Furthermore, even if God is not “an immediate cause” of sin, He may be an intermediary cause, and that seems, at least superficially, contrary to His benevolence (III:46).

Despite these infirmities, which may or may not have been addressed in the two philosophers’ other works, Locke and Berkeley’s discussion of material substance meaningfully furnishes students of philosophy with additional understanding of the limits of their own mind.

Reference Notes

(9) refers to Book 2, Chapter 8, Section 9 of Locke’s An Essay Concerning Human Understanding.

(I, 2) refers to First Dialogue, Page 2 of Berkeley’s Three Dialogues between Hylas and Philonous.